During the colonial period a fiercely contested dispute over the ownership of the waterways along the coasts of Maryland and Virginia and the bounty (oysters) which lay within them resulted in the “Oyster Wars”. Read more about the Chesapeake’s fascinating feud, ‘oyster pirates’ and more in this story by Kathy Warren, for the Summer 2008 Southern Maryland This is Living Magazine.

The Infamous Oyster Wars

Printed with kind permission of Southern Maryland This is Living Magazine.

Around the world and throughout history the oyster has played a significant role in the lives and livelihoods of both royalty and peasants. The popularity of this small filter feeding bi-valve dates back thousands of years when it served as a dietary staple during the Neolithic period. Roman emperors traded gold for oysters, and their guests were said to have gorged on oysters brought back by slaves from the fertile shores of England.

The mystical powers of the oyster have been touted throughout the ages where they were deemed to be both medicinal and a powerful aphrodisiac. The word “aphrodisiac” comes from Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and beauty who is said to have risen from the sea on an oyster shell to give birth to Eros, forever connecting oysters with romance.

Although the well heeled have long enjoyed these delicacies, the oyster also has a more humble and practical side. Once found in abundance throughout the world, the oyster was a common food found in many homes. Native Americans living near waters where oysters thrived used the oysters to supplement their diets when other game was scarce.

Maryland, with its many tributaries and nearly ideal conditions for growing and sustaining oysters, was once one of the most prolific oyster producing areas of the world. So it’s no surprise that when settlers first came to the region they were struck by the shear numbers of oysters found across the region. Discarded oyster shells were so numerous during the colonial era that they created artificial reefs or “middens,” which sometimes grounded ships. It was also during the colonial period that the stage was set for what would later become a sometimes bloody dispute over the ownership of the waterways along the coasts of Maryland and Virginia and the bounty which lay within them resulting in what is commonly known as the Oyster Wars.

In 1632, Cecil Calvert obtained a charter that granted the newly established colony of “Mariland” control over the upper Chesapeake Bay and the Potomac River. Virginians, who felt they should have the water rights to the bay, campaigned heavily to maintain interests they believed rightfully belonged to Virginia, and managed to maintain control of the strategic lower portion of the bay. This would prove to be a bone of contention for both Maryland and Virginia for years to come, with each colony and later each state, flexing its political muscle through regulation of “their” sections of the tidewater region.

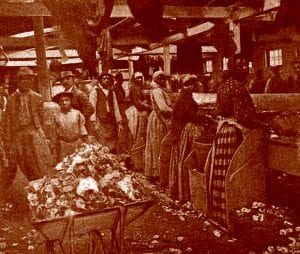

Throughout the 1800s and well into the 1900s oyster shucking and packing houses could be found all along the shoreline of Maryland and Virginia. Newly freed slaves, whites, and immigrants labored side-by-side working long hours with little pay to fill the demands for oysters from as far away as Australia. Even the shells themselves became a commodity as farm fertilizer and for use in mortar.

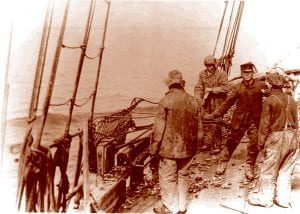

Watermen, often known as a rough and bawdy lot, made their living from the water often under harsh conditions and amidst several major wars. It was hard work harvesting oysters, and often men were tricked into working on boats only to be left along the shoreline with no pay. Another more sinister method of payment was called “paid by the boom,” meaning that after a stint aboard a boat, the worker would mysteriously fall overboard, never to be heard from again.

Tonging, the method of pulling up oysters from deeper waters with the use of long metal or wooden rake style tongs, became the preferred method for collecting oysters along the Chesapeake and Potomac waterways. As the demand for oysters grew, so did the ingenuity of the watermen harvesting them.

In the early 1800s a new method for collecting oysters known as “dredging” came into favor in the Northeast. This new contraption with its metal teeth, and mesh style basket could be dragged from a sailing vessel and reeled in, yielding a much larger catch with less effort. Though initially designed to collect only oysters in deeper waters, it was soon misused in shallower waters where it quickly destroyed the oyster’s natural habitat. Watermen from New York and as far north as Connecticut, soon found themselves without the commodity they needed to sell, and began working their way further south, eventually landing along the shores of Maryland and Virginia. The debate between dredgers and tongers would only add fuel to the fire and spawn future conflicts.

The practice of dredging prompted Maryland lawmakers to enact legislation preventing non-residents from harvesting oysters along their waterways and led to the beginning of the Oyster Wars. With the passage of the Acts of 1820, the legislature attempted to stem the tide of New England watermen and their wanton disregard for the preservation of the shellfish. Oyster pirates, known as the Mosquito Fleet, largely ignored the new laws and continued to dredge, mostly under the cover of night.

Finally, in 1868, the State Oyster Police Force was created with former Naval Academy graduate Hunter Davidson serving as the first commander. In 1874, the oyster police force was restructured and renamed the State Fishery Force, and is today known as the Maryland Natural Resources Police. Captain Amos Creighton served as commander of the oyster police from 1912 until 1952.

The oyster police took their responsibilities very seriously and used several ships including the Governor R.M. McLane, which was built in 1884 for the U.S. Navy and outfitted with a 12-pound howitzer on her deck. It was purchased by the state of Maryland and used by the oyster navy to patrol the waters along Maryland’s coast looking for violators. Citizens became so upset over the powerful gun that it was eventually removed. This game of cat and mouse between law enforcement and the watermen was often heated and sometimes even deadly.

The battles over who had the right to oyster where, and dredgers versus tongers, continued well into the 20th century pitting the police against the watermen as well as Marylanders against Virginians. An article in The Washington Post dated 1947 reads: “Already the sound of rifle fire has echoed across the Potomac River. Only 50 miles from Washington men are shooting at one another. The night is quiet until suddenly shots snap through the air. Possibly a man is dead, perhaps a boat is taken, but the oyster war will go on the next night and the next.”

Although the police and illegal dredgers sometimes scuffled with one another, as well as watermen fighting other watermen, there remained a sense of civility and dignity amongst them all, each respecting one another’s need to make a living. By the 1960s, under the Potomac River Compact of 1958, legislation was enacted allowing dredging of the Potomac River and effectively bringing an end to the earlier conflicts. Many Maryland watermen feel that this was the beginning of the end for small independent oystermen in Maryland.

Today, natural events such as hurricanes, lowered salinity levels and diseases have markedly decreased the number of oysters, which were once so plentiful. Human causes such as over harvesting and increased pollution have also contributed to the decline in oysters in the Chesapeake and Potomac.

Efforts by conservationists will hopefully bring the beloved oyster back to a sustainable level, but the days of our waterways being dotted with skipjacks and bugeyes bringing home the day’s catch seem a distant memory for many. The oyster wars of this century will entail saving a piece of our history for generations to come.

For further reading on the topic: “SlackWater Volume IV: Crassostrea virginica,” Spring 2004, St. Mary’s College of Maryland and “The Oyster Wars of Chesapeake Bay,” by John R. Wennersten.